Illustration: Andrea Brunty, USA TODAY Network

Two years ago, a report by Louisiana State University’s lead Title IX investigator showed that top athletic department administrators skirted the school’s sexual misconduct policies by keeping allegations against athletes in house.

Yet LSU did nothing to correct the problem at the time, USA TODAY found. It required no additional training for athletic department officials. Nor did it investigate whether the same officials had mishandled other allegations against athletes.

Now, LSU is under fire after a USA TODAY investigation found officials in the school’s athletic department and broader administration repeatedly ignored complaints against abusers, denied victims’ requests for protections and subjected them to further harm by known perpetrators. In response to the investigation, LSU is paying an outside law firm, Husch Blackwell, up to $100,000 to review cases and determine whether any wrongdoing occurred.

LSU Interim President Tom Galligan told USA TODAY he “really wasn’t aware” of the university’s problems handling sexual misconduct until the news organization published its investigation last month. Both Galligan and LSU’s Board of Supervisors have promised accountability for any LSU officials found to have mishandled allegations.

But the November 2018 Title IX report, obtained by USA TODAY, demonstrates that the school has long known of the problem and that LSU took no action when athletic department officials violated Title IX policies in the past.

The report shows that deputy athletic director Verge Ausberry and football recruiting director Sharon Lewis admitted it was their practice to steer allegations against athletes to Miriam Segar, a senior associate athletic director, instead of reporting them directly to the Title IX coordinator, as LSU policy requires.

Ausberry also told the investigator that when a female student came to him because she had been abused by football player Drake Davis, he told her he “didn’t want to hear anymore” and to talk instead to Segar, who acknowledged never returning the student’s call.

The investigator found Lewis responsible for violating LSU’s Title IX policy because she had failed to report the allegations against Davis to anyone when she learned about them in 2016, the report shows. But LSU took no disciplinary action against Lewis, her attorney told USA TODAY.

The report does not say whether Ausberry or Segar were investigated regarding their admissions they were not following Title IX policy. LSU spokesman Jim Sabourin declined to answer whether an investigation had ever occurred but said that neither was found responsible.

LSU has since promoted Lewis and Ausberry. Segar remains in her current role. Ausberry also sits on the committee that will select a new LSU president – a president who will be tasked with ensuring that any reforms recommended by the outside firm are carried out.

In an interview with USA TODAY, Galligan was unable to point to a single action or measure that the university has taken in the two years since the report to address the problems it identified.

“We remind people that everybody who is a responsible party has an obligation to report,” Galligan said. “We’ve probably done the same things for the last few years but tried to do them – tried to emphasize. Certainly we’re emphasizing them now.”

Top LSU athletics officials and their bosses

Neither Galligan nor LSU would answer specific questions about the November 2018 case. When asked for any evidence that the university took action to bring the athletic department into compliance with the law and its own policies, LSU provided none.

“We now continue to reinforce that every LSU employee, with extremely limited exceptions for those in designated, confidential roles, is required to report knowledge of a sexual or domestic assault to the Title IX office,” Sabourin said.

The directive to report sexual misconduct allegations to Segar, instead of the Title IX office, came from the highest level of the athletic department, according to documents LSU provided to USA TODAY.

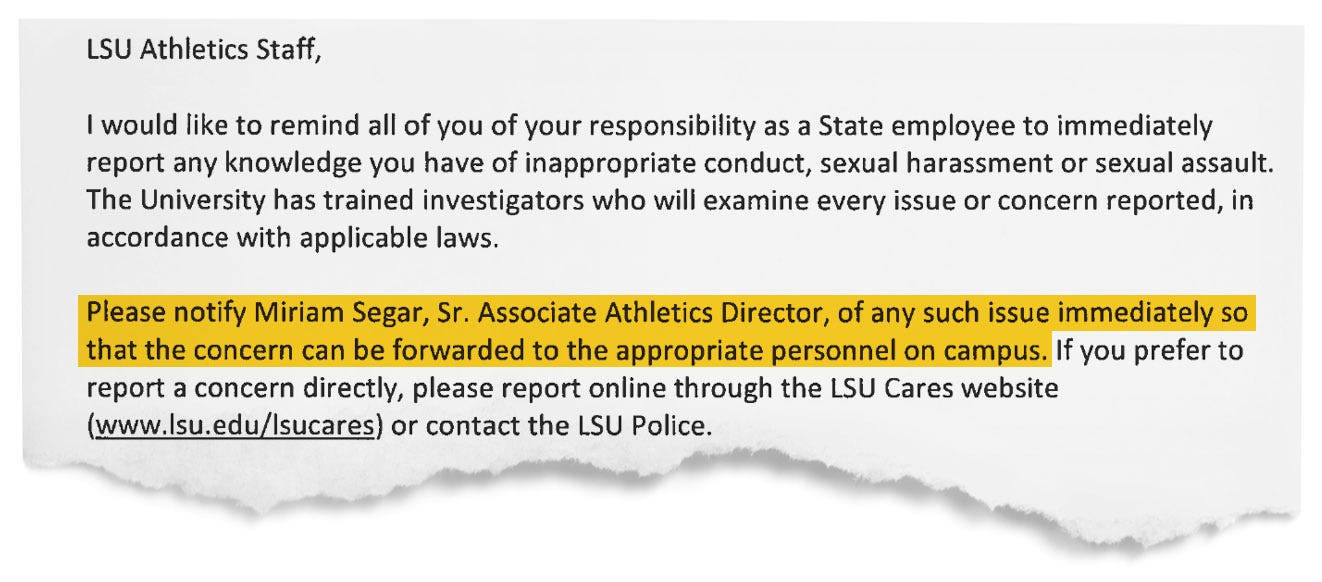

In a 2016 email and a 2018 letter to athletic department staff, then-Athletic Director Joe Alleva reminded employees of their responsibility to report all allegations of sexual misconduct, but instructed them to share the information with either Segar or the athletic department’s head of human resources.

“Please report these issues to either Miriam Segar, Sr. Associate Athletics Director Student Services or Wendy Nall, Assistant Athletics Director HR,” Alleva’s 2016 email said. “Both of these individuals have been trained in Title IX law and university protocol for investigation and can help facilitate the proper reporting that is required by law and University policy.”

The federal law known as Title IX, which prohibits sex discrimination in education, and LSU’s own policies since 2014 require school officials to report all sexual assault and dating violence allegations directly to the Title IX coordinator for investigation. The policies specifically bar athletic department officials from being involved in the handling or investigation of complaints against athletes.

Using an athletic department official as a middle man for sexual misconduct complaints against athletes amounts to “impeding the university’s ability and obligation under Title IX to promptly investigate and eliminate sexual violence,” said Elizabeth Taylor, a Temple University professor who studies sexual assault within athletic organizations.

“It’s a huge conflict of interest for the athletic department,” Taylor said. “They were essentially allowing this senior associate athletic director the ability to make decisions about whether or not to continue to report things up the chain. They’re playing the decisionmaker when it’s not their decision.”

Alleva did not return multiple calls or a text message. He stepped down as athletic director in April 2019 and into a transitional role of special assistant to the president for donor relations. He is no longer employed at LSU.

USA TODAY’s previous reporting found that Ausberry, Segar and Lewis each failed to share other sexual misconduct and violence allegations against Davis and another football player, Derrius Guice, with the Title IX office before the November 2018 report. But the school has not investigated those breakdowns until now.

The Title IX report was not the only warning sign LSU ignored.

In 2017, a Louisiana nonprofit sexual trauma survivor advocacy group named STAR told the university it had concerns with the athletic department's handling of sexual assault prevention efforts.

In a letter addressed to top LSU officials – including the then-university president, Alleva and head football coach Ed Orgeron – the group detailed two incidents it found troubling. The first was a planned sexual assault awareness presentation featuring an athlete accused of rape in a high-profile case at another university. The second was a tweet by Guice, LSU’s star running back, that cast doubt on rape allegations against a high school classmate who had just been indicted by a grand jury.

STAR said it never got a response.

In 2018, David Lewis, father of former LSU women’s tennis player Jade Lewis, complained to the Southeastern Conference and the NCAA about LSU’s failure to protect his daughter from Davis. Jade Lewis dated Davis in 2017 and 2018, during which time Davis repeatedly abused her while university officials stayed silent.

David Lewis said the SEC forwarded his complaint to LSU, but LSU never responded.

Davis pleaded guilty in 2019 to two counts of battery against Jade Lewis. Prosecutors dropped other charges against him in exchange.

By that time, athletics department officials already knew about Davis’ dangerous behavior.

LSU dropped the ball

In the case that sparked the 2018 Title IX investigation, then-LSU student Calise Richardson reported her former boss, Sharon Lewis, for failing to share her allegations of dating violence against Davis with the Title IX office two years earlier.

Had Sharon Lewis reported it at the time, the school might have acted sooner to stop Davis from repeatedly assaulting Jade Lewis in 2017 and 2018.

Sharon Lewis is not related to David and Jade Lewis.

It is USA TODAY’s policy not to publish the names of people who allege sexual or dating violence without their permission. Richardson and Jade Lewis chose to use their full names.

“I did what I was supposed to do,” Richardson said. “LSU is saying, ‘We didn’t know about these things, or we could have fixed them.’ We did report them. We did win. And you guys still did nothing.”

Richardson had worked in the football recruiting office since her freshman year, 2014, one of several dozen student employees who supported recruiting efforts by doing administrative work and interacting with prospects and their families.

In the summer of 2016, Richardson said, she met Davis, a freshman who had turned down offers from Alabama, Ohio State and others to play football for LSU in his hometown of Baton Rouge. They started dating, but Davis was controlling and verbally abusive, she said, and physical abuse soon followed.

Richardson said Davis on multiple occasions pinned her against a wall by her neck, and other times, he would prevent her from leaving by physically restraining her or blocking a door. She said she initially did not tell anybody about the abuse.

But a friend of Richardson’s who also knew Davis told USA TODAY that both had made comments indicating there were problems.

“She had told me she was scared,” said the friend, who asked to remain anonymous in the story out of concern for potential employment repercussions. “Drake would make comments like, ‘You know how I get when I get mad.’ … Whenever she’d say, ‘I was really scared of him last night,’ I could piece it together.”

Davis denied Richardson’s allegations in text messages to USA TODAY.

After a football game in October 2016, Richardson said she went with some other friends on the team to JL’s bar in Tigerland, an area about a mile from campus popular with students for socializing and drinking.

Davis was there, and Richardson said she saw him kissing another woman when she arrived. Richardson said she brushed Davis off when he approached her, which made him angry.

“He two-hand pushed me, and I flew back and fell on the floor of the bar,” Richardson said.

They threw drinks at each other and were yelling, and teammates had to restrain him, she said. The bar manager kicked Davis out, while she stayed behind.

When she left that night accompanied by another player, Davis “comes out of nowhere and charges me,” Richardson said. Again, teammates restrained him, she said. Davis showed up at her apartment that night, she said, and she had to call teammates to come get him.

The following morning, Richardson got a phone call from Sharon Lewis, one of her bosses in football recruiting, who asked why she attacked Davis. Lewis said players told their coach that Richardson had thrown a drink at Davis, according to the Title IX report two years later.

Richardson said she told Lewis that Davis was the instigator. Lewis asked if Richardson wanted to meet with him and his then-coach, Dameyune Craig, to “iron things out,” the Title IX report shows. Richardson declined but said she met with Lewis and another of her bosses, Keava Soil-Cormier, to tell her side of the story.

“They never once asked me if this was the only time he’d ever been physical,” Richardson said. “They never offered me resources of, ‘This is who you can call and get help from.’ They didn’t ask if I felt safe or not.”

Richardson said Lewis and Soil-Cormier told her she could go to the police, but she didn’t feel the suggestion was sincere.

“It was in a manipulative way. Like, ‘If you feel this is worth ruining his future, we can call the cops,’” Richardson recalled.

She said no. As the meeting ended, Richardson said, she told Lewis and Soil-Cormier she was afraid of Davis.

“I told them, ‘He lives down the hallway of me at my apartment. I’m scared of him.’ And, I remember it so vividly: They laughed,” Richardson said. “Like, ‘Are you serious?’ So dismissively. I wasn’t ready to tell people about my (abusive) relationship, but I was asking for some type of help, and they laughed it off."

Sharon Lewis declined to comment for this story through her attorney. She told the Title IX investigator that she did ask Richardson during the meeting if she felt threatened by Davis and that Richardson told her no, according to the Title IX report.

Soil-Cormier declined to comment to USA TODAY.

LSU’s policy requires employees who witness or are told about possible sexual misconduct or dating violence to notify the school’s Title IX coordinator, who conducts an initial investigation. But Richardson said no one from Title IX ever contacted her.

The Title IX investigation two years later revealed that the Title IX office had no record of the allegation.

Ausberry ‘didn’t want to hear anymore’

In the fall of 2018, Davis was arrested on charges of repeatedly assaulting Jade Lewis, the former LSU tennis player.

Upon learning of the abuse, Richardson went to Ausberry, a mentor, in tears. She, too, had been abused by Davis, she told Ausberry, then the deputy athletic director.

“It was a wave that came crashing down,” she said. “I felt so responsible for Jade’s pain. If I would have pushed harder back then, if I had kept pushing and kept talking and didn’t take no for an answer, maybe this wouldn’t have happened.”

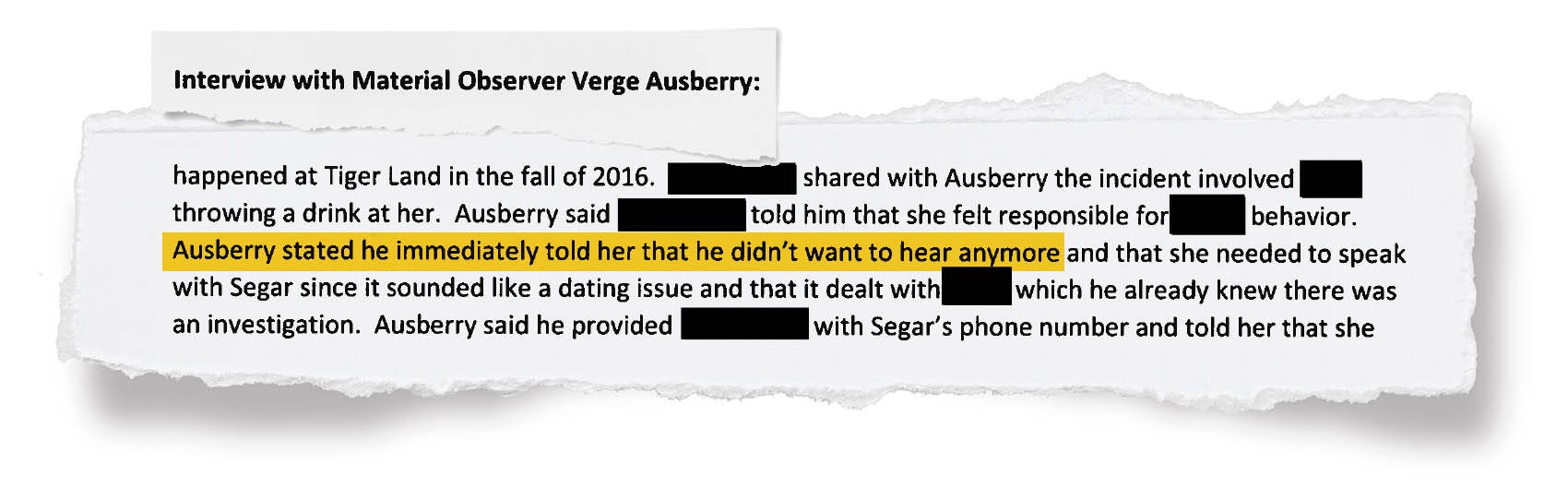

But Ausberry, according to the Title IX report, stopped her.

“Ausberry stated he immediately told her that he didn’t want to hear anymore and that she needed to speak with Segar since it sounded like a dating issue and that it dealt with (Davis) which he already knew there was an investigation,” the report reads. “Ausberry said he provided (Richardson) with Segar’s phone number and told her that she really needed to disclose this information to Segar.”

Richardson disputes that Ausberry gave her Segar’s phone number.

A few days later, Richardson said she got a voicemail from Segar.

“I immediately called her back and I never heard from her again,” Richardson said. “Never called me back, never emailed me, nothing.”

When Title IX investigator Jeffrey Scott interviewed Segar, she said that she and Richardson had “played phone tag” but never spoke.

On Oct. 1, Richardson said, she broke down in the office of Brenton Sumler, manager of the athletic department’s Life Skills program, and told him everything. She said he immediately took her to an assistant dean of students who helped her file a Title IX complaint against Sharon Lewis.

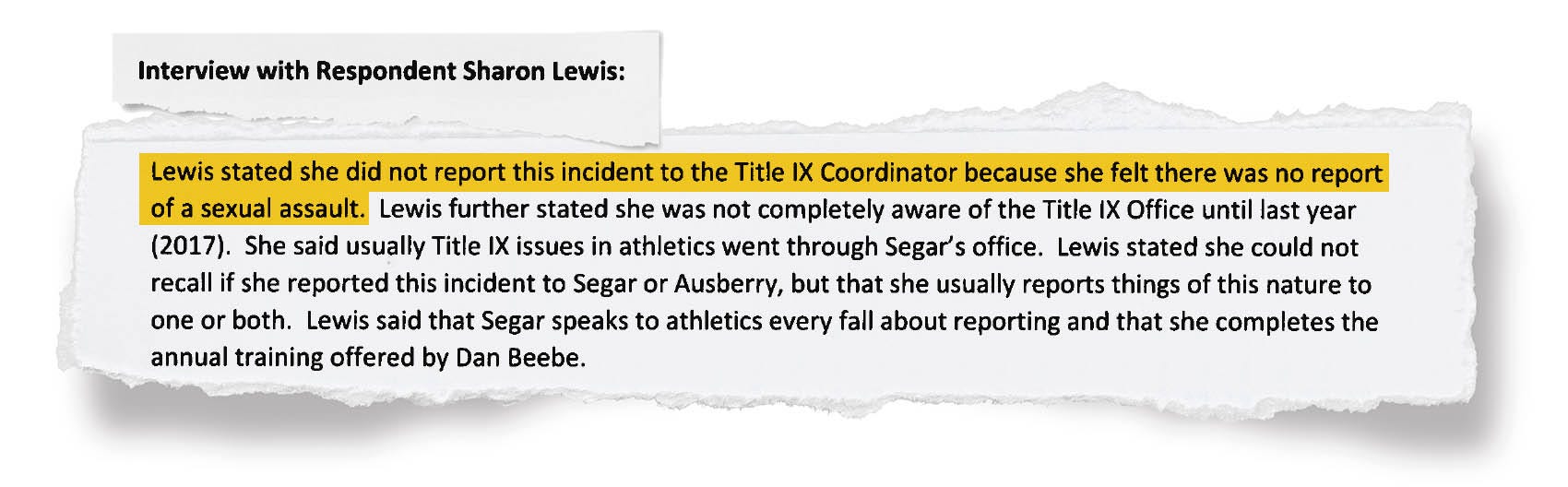

When questioned by Scott, Lewis said she hadn’t reported the incident between Richardson and Davis in 2016 because “she felt there was no report of a sexual assault,” according to the Title IX report.

“Lewis further stated she was not completely aware of the Title IX office until last year (2017),” the report states. “She said usually Title IX issues in athletics went through Segar’s office. Lewis stated she could not recall if she reported this incident to Segar or Ausberry, but that she usually reports things of this nature to one or both.”

In an investigation report dated Nov. 16, 2018, Scott determined that Lewis violated the school’s Title IX policy when she “failed to report” Richardson’s dating violence allegation against Davis in 2016. But Lewis’ attorney, Maria Finley, told USA TODAY last month that LSU’s human resources office declined to issue any punishment against her.

Without providing evidence or specifics, Finley called LSU’s Title IX investigation “flawed.” She said other case documents prove Richardson is “making things up” but wouldn’t provide them. Finley confirmed that Lewis lost her appeal and that the Title IX violation remains on her record.

LSU promoted Lewis from assistant athletic director to associate athletic director in August. She remains LSU’s head of football recruiting.

Allegations kept in-house

In response to USA TODAY’s November investigation, head football coach Ed Orgeron said LSU employees have both a “legal and moral” obligation to report all allegations of sexual misconduct and dating violence to the Title IX office for investigation.

“When we become aware of accusations, we have an obligation to immediately report every allegation to the University’s Title IX office so that appropriate due process can be implemented,” he said in a statement to USA TODAY.

Yet the 2018 Title IX report shows that Lewis and Ausberry had a practice of reporting such allegations not to the Title IX office, but to a point person in athletics: Segar. That was also the guidance from Alleva, the former athletic director, his written messages to staff show.

Segar, however, has not always relayed those allegations to the Title IX office, USA TODAY found.

In July 2016, Samantha Brennan, a student worker in the football recruiting office, learned Guice, the LSU running back, had taken a partially nude photo of her without her consent and shared it with at least one other person. According to Brennan and text messages she shared with USA TODAY, Lewis found out about it and brought Segar in to talk to her about it. Segar then accompanied Brennan to the LSU Police Department to file a report.

Lewis and Segar were still required to report the incident to Title IX. Brennan has told USA TODAY that no one from the Title IX office ever contacted her.

During the 2018 Title IX investigation, Segar told the investigator Lewis “has never reported any Title IX/Sexual Misconduct issue to her.” Yet Lewis did report at least one incident to Segar: the photo of Brennan that Guice had taken and shared.

Segar and Ausberry were also among seven LSU officials with firsthand knowledge in April 2018 that Davis had physically assaulted Jade Lewis, the LSU tennis player he started dating a year earlier.

Jade Lewis directly told Segar and two other athletic department employees on April 25, 2018, that Davis had punched her on multiple occasions over a yearlong period, according to August 2018 police records. That included at least one incident in her on-campus apartment. Because it occurred on campus, a federal law known as the Clery Act required the officials to immediately report it to the LSU Police Department, but the department’s public crime logs do not list it.

Segar did file a Title IX report in April 2018, but the Title IX office waited more than two months to interview Davis, records show. By then, Davis had assaulted or strangled Jade Lewis at least three more times, she told police and USA TODAY.

It wasn’t until Aug. 16, 2018, after Jade Lewis showed Segar photos of bruises and scratches she said Davis had given her, as well as text messages in which he threatened to kill her, that Segar called campus police. Davis was arrested the following day and charged with felony dating violence.

A search warrant obtained by LSU police detectives the following month revealed that Ausberry, the deputy athletic director, had been sitting on a text message confession from Davis for more than four months. On April 14, 2018, Davis texted Ausberry admitting to punching Jade Lewis in the stomach, according to the police report.

But Ausberry never reported the incident to the Title IX office or police. In July 2019, Ausberry was promoted to executive deputy athletic director and executive director of external relations for the university. He earns $500,000 a year.

Richardson said learning that the same LSU officials had stayed quiet about both her and Jade Lewis’ abuse was “traumatizing.”

“If mine was an isolated incident, maybe we could argue that they were being careful, they didn’t want to hurt me,” Richardson said. “With how many cases this is, they know what they’re doing.”

If you have a tip or sensitive information you want to share, reach out to USA TODAY Sports at SportsTip@usatoday.com. You can also contact the reporters directly, narmour@usatoday.com for Nancy Armour or kjacoby@gannett.com for Kenny Jacoby.